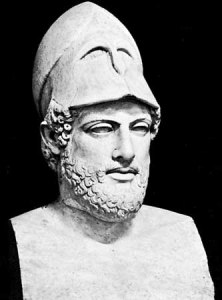

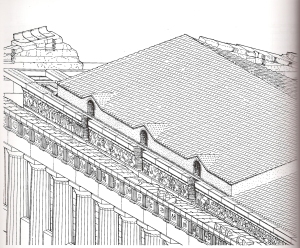

The temple of the Parthenon was built in the 5th century B.C. on the Acropolis Rock, and was dedicated to the goddess Athena Parthenos, the virgin patron goddess of Athens. The Acropolis was originally the inner fortress of Athens, but also hosted the most important sacred and ceremonial activities of the city. After the victorious conclusion of the Persian Wars (490-479 B.C.) when the city-states of Hellas repulsed the invading armies of the Achaemenid Persian Empire, the Athenian Democracy under the leadership of Pericles, decided to rebuild the whole Acropolis complex which had been destroyed by the invading troops. The Parthenon was built between the years 447 and 438 by the architects Ictinos and Callicrates, with strong personal involvement by Pericles himself. The 69.5 x 30.9 m rectangular building was made of local white marble in the Doric Order with single-rowed colonnades all around and double-rowed porticoes supporting triangular pediments at either end. The architectural details and the construction accuracy were of the highest standard, indicating employment of first rate technicians from all over the Greek world. Long before the temple’s completion the sculptor Phidias undertook to further embellish the building with extensive decorations of the frieze, the metopes and the pediments, with scenes drawn from the Greek mythology and local foundation myths, in high relief all brightly painted.

Athens retained an acknowledged role as the cultural centre of the Hellenic world long after the Roman conquest. In 395 A.D. the invading Gothic armies of Alaric, reached Athens, but spared the Acropolis without causing any damage to its temples. In the year 529, long after the Christianizing of the Roman Empire, the philosophical schools of Athens were ordered closed and the traditions of classical Athens were finally extinguished.9 Parthenon was converted to a church, dedicated to “Our Lady of Athens”. Much of the sculptural decorations were deliberately defaced or destroyed at that time, (especially the east pediment) presumably for depicting clearly pagan scenes, whereas others were inexplicably spared and adopted into the church imagery.

In 1204 the Fourth Crusade occupied Greece, and the Parthenon was converted to the Roman Catholic church of Notre Dame.

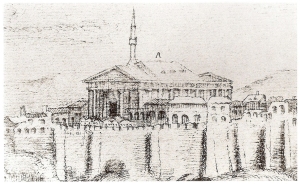

In 1458 the Ottoman Turks captured Athens and the Parthenon was again converted to a mosque, with a minaret added on top.

In the 17th century the first European travelers began arriving from the West, with a keen interest in classical antiquities. Until that time the Parthenon was almost complete, and an artist accompanying a French ambassador to Constantinople in 1674 was able to make extensive sketches of the Parthenon frieze and the metopes. These sketches by Jacques Carrey were to prove invaluable for depicting much material that is now lost forever.

The 17th century was marked by a series of wars between the Turks and the Venetians. In this context the Turks had fortified the ancient fort of the Acropolis, turning the strongest building-the Parthenon- into their gunpowder magazine. The Venetian general Francesco Morosini was besieging the Acropolis and on 26th September 1687 a cannonball struck the Parthenon and the whole building exploded. The huge gap now visible in the middle of both long colonnades was created that day. Several columns were shattered and much sculpture completely destroyed. When the Turkish garrison surrendered, Morosini attempted to remove the surviving west pediment to take back to Venice as a trophy of his conquest. However as they were lowering the huge piece of marble the cables broke and it shattered on the ground. Morosini was only able to take back one head of Apollo (which is now in the Louvre) before handing Athens back to the Turks. The Turks used the debris to build a second smaller mosque inside the Parthenon, this time at an angle to the main building so as to align with the direction of Mecca. The heaps of fallen pieces of marble provided ready building materials to repair the fortress walls and were also suitable for burning into lime. The explosion also revealed that the ancient builders had used lead to connect the marble drums of the columns. This material could be extracted to make musket balls leading to further destructions of the monument.

The dispersed fragments soon attracted the interest of western European travelers, willing to pay for original Phidias pieces. There was considerable dispersion mostly of small Parthenon fragments in the 18th century. Several have been recently identified in Palermo, Padua, Paris, Karlsruhe, while some have been literally unearthed in English country houses’ gardens.

The end of the 18th century witnessed a booming antiquity market in Athens. The French ambassador in Constantinople, had set up his own agent in Athens, with instructions to draw, make casts and especially to remove all the Parthenon sculpture for shipment to France. The French Revolution cancelled the ambassador’s plans. France was soon at war with Turkey and it was Britain’s turn to set up an agent in Athens.

The new British ambassador to Constantinople, Thomas Bruce, the 7th Earl of Elgin, has his name linked to the Parthenon much more than to his diplomatic career. His term at the Ottoman capital coincided with Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt (1798-1802), and therefore with the breaking of the traditionally cordial Franco-Turkish relations. As a principal allied representative, Elgin was to enjoy great privileges and influence at the Sublime Porte of the Sultan Selim III. Of a Scottish noble family, Elgin even before starting for the Levant was set to make his embassy a tool for the advancing of knowledge of Greek Architecture in Britain. He privately employed the landscape painter G.B. Lusieri from Sicily to put in charge of a team in Athens.

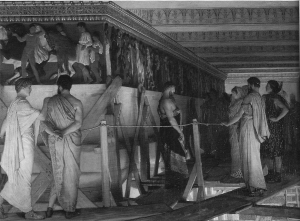

Arriving at Athens in August 1800, the group set to work. Elgin’s influence secured one and then a second official letter (firman) from Constantinople overruling the objections of local officials and their demands for bribes and giving his team unlimited access into the Acropolis fortress. While initially only taking casts and measurements, the group gradually proceeded to collecting marble pieces and inscriptions lying about, then digging for more and finally the decisive move was made on 31st July 1801 when the first metope (the one at the SE corner and one of the best surviving-) was sawn off from the standing building by a ship’s carpenter and lowered to the ground. Elgin’s secretary wrote triumphantly to his master that they had beaten the French to it and that upon reaching home safely” … must prove of inestimable service in improving the National Taste”.

Hectic activity on the Hill followed. Turkish soldiers’ houses with incorporated ancient marbles were bought just to be pulled down. When one soldier was unwilling to sell, a firman from the capital obliged him to. The excavations soon discovered the huge figures from the west pediment, which had survived from the explosion of 1687 and the subsequent attempts by Morosini at removing them. Then saws were specially ordered from Constantinople so that the reliefs of the frieze, which had been carved directly on the huge structural blocks of marble, could be sawn off. Since the group did not possess real engineering knowledge, they were unable to remove some fine pieces like the metope at the SW corner. Two other easily accessible pedimental figures were left in place because they had the wrong information that they were later Roman additions, while in fact they are originals.

Elgin left Constantinople in early 1803, but he was arrested by the French on the way home and was detained until 1806. When released to return to England he faced bankruptcy.

The last shipment of his marbles collection arrived in England in May 1812. With his Parthenon collection reunited, he put them on display in a London house and they immediately created a sensation among artists, architects and the fashionable society who were unanimous in their praise:. “The finest things that ever came to this country”, “The finest works of art I have ever seen”, “infinitely superior to the Apollo Belvedere”.

With his financial situation worsening however Elgin had to resort to selling his collection to the government. An Act of Parliament was passed transferring the ownership of the Parthenon collection to the nation and in August 1816 the marbles were moved to the British Museum.

really good overview of what this masterpiece went through.. Even after all this brutality, it still remains a beauty..